The COP26 in Glasgow did almost everything it could, but in the same time it didn’t. This is a short summary of the outcome of the 26th annual Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the COP26 in short. We at the Green Policy Center have evaluated the results of the conference shortly below, while the most important topics are explained in more detail in the following article. At the end you can also find a gallery of our personal impressions of the COP26.

I. The main results of COP26 in brief

POSITIVE:

- after a year’s gap, amid extremely heightened expectations and a tense mood, the world has been reunited, both physically and diplomatically to discuss climate change;

- despite the many contradictions and challenges, a joint declaration (which is not a new Paris Agreement) has been adopted and the implementing rules of the Paris Agreement have been completed and finalized. Thus, there is no longer any regulatory ambiguity ahead of implementation;

- some vague hope remained to stay below 1.5 ° C of global warming;

- it should be emphasized that both India (2070) and China (2060) and the rapidly growing Nigeria (2060) have committed themselves to a climate neutrality target and with this around 90% of countries already have such a target;

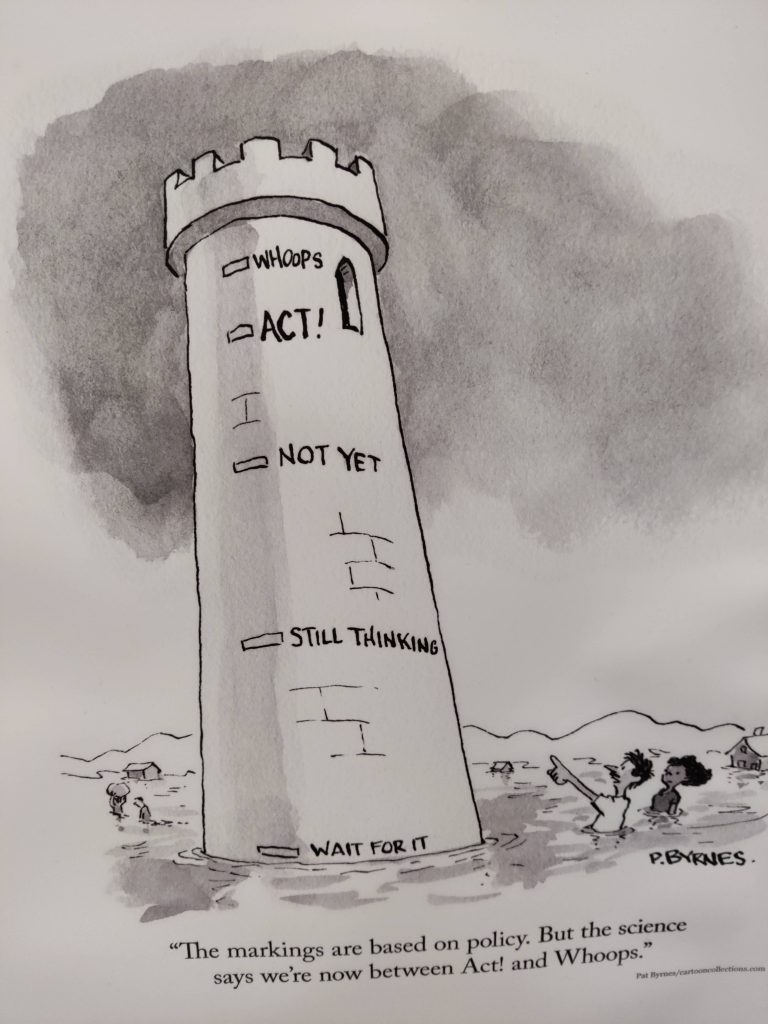

- if the Nationally Determined Contributions now announced are fully complied with, global average temperature increase could be kept as high as 1.8 ° C until 2100 according to the IEA, but 2.4 ° C is more likely, as the Climate Action Tracker estimates. For comparison, this figure before COP26 was around 2.7 ° C;

- for the first time, the issue of fossil fuels has been included in a legal text, as so far Saudi Arabia or the United States were blocking its inclusion;

- the challenging series of negotiations on market and non-market approaches on carbon emissions trading described in Article 6 of the Paris Agreement have finally been closed. The worst and biggest shortcomings have been addressed, but countries and companies still have the opportunity to maintain their current levels of emissions;

- the two current biggest emitters, the US and China have issued a joint statement, which can be seen as a hopeful and strong signal to the whole world about the “seriousness” of the process;

- a significant part of the world’s countries, including Brazil, have agreed to end deforestation by 2030, bringing a total of 85% of the world’s forests under protection;

- it is also an important step that more than 100 countries around the world have committed to reduce their methane emissions by at least 30% by 2030. As methane is the second main greenhouse gas responsible for climate change after carbon dioxide, this step is absolutely important to avoid the climate catastrophe.

NEGATIVE:

- no real breakthroughs have taken place in the process, practically it has been only agreed that much remains to be done;

- the “Glasgow Climate Pact” has been weakened at the last minute. The final text only provides for a phasing down unabated coal use and not phasing it out due to a last-minute intervention by India, who has just now been forced to impose a 2-day curfew because of poor air quality in the country. There are already astonishing misunderstandings because of this amendment, for example, some interpret it as giving coal-fired power plants a green light to continue operations;

- global carbon dioxide concentrations have been rising sharply for 200 years. As David Attenborough has pointed out, this is the most important metric and if it doesn’t start to stagnate and then to go down, the whole process will definitely not be a success. Each commitment will be worth as much as it can positively effect this number;

- according to the International Energy Agency, the IEA, only 20% of the commitments needed by 2030 to keep 2050 net zero goal (i.e. 1.5 degrees) have been submitted so far. Again, much remains to be done;

- although negotiations under Article 6 have been concluded, there are currently no strict and uniform rules for companies to offset emissions, so more and more ‘greenwashing’ is taking place because everyone feels that greening is expected. Processes could also fail, if they are not transparent enough both in the public and private sectors.

II. Detailed assessment of some important areas

1. Emission reduction and the future role of coal

It has been recorded that the commitments made by the countries so far are not sufficient to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement. They should be re-examined by the Parties by 2022 and they have to return with new commitments. It was not realistic that this matter would be resolved during the COP, but the question remained as to who should do more and by how much. Raising emissions will be a challenge for players like China or India, but this may also cause difficulties within the EU (see the current debate on energy prices).

However, some, including the COP Bureau, assessed that the 1.5-degree target had been kept alive. At the same time, the hope will only live on if the processes will start to go in the right direction in the next 1-2 years. Without this beyond a point reaching our goals and not passing the tipping points will no longer be realistic. It is also an important in this matter what kind of emission curve the commitments will draw up to 2030 in order to reach the 2050 targets.

The inclusion of coal phase out was blocked at the last minute by China and India, so only a phasing down of unabated coal was included in the final document, plus with no time limit. It is definitely a disappointment not to adopt a measure that is so clearly needed. Surprisingly, however, this was the first time that fossil energy had appeared in an official, adopted COP document.

2. Financing

The US$ 100 billion annual target has not been met so far (of course, there has been and will be an eternal debate on what and how should be counted as climate finance) and no agreement has been reached to compensate for the part that has not been met so far. To address this, a “Climate Finance Delivery Plan” has been presented in order to deliver on the climate finance commitments of developed countries made back at the COP16 in Cancun to mobilise yearly US$ 100 billion by 2020 and thereafter. The Paris Agreement updated the target to 2025 and the Delivery Plan states that this goal will be already met in 2023 and then annually after 2025. On the positive side, the share of funding for adaptation has been raised to 50% of the total climate finance envelope, which is important for developing countries, especially those that have virtually no emissions and are only suffering from the negative effects of climate change.

3. Loss and damage

This brings us to the subject of loss and damage, which is a sensitive and particularly important issue of ‘climate justice’ for the smallest developing countries. However, the breakthrough they have hoped for has not been achieved. Developing countries are demanding compensation for the costs of loss and damage caused among others by cyclones and sea level rise. According to small island states and climate-sensitive countries, these effects have been caused by the historical emissions of industrialised countries, so their compensation is needed. Their goal is to create a dedicated financial instrument for this purpose. Developed countries however fear that the process will provide a basis for “pricing” historical responsibilities and possibly enforcing them in court so they have vetoed setting up a new tool at COP26.

At the same time, a dialogue is emerging, which will be certainly a basis of much debate in the future and may affect the achievement of the goals.

4. Paris Rule Book

It is certainly positive that the implementation framework of the Paris Agreement is now in place in all areas. This was a necessary but far from sufficient condition for the commitments to be implemented by the Parties in a regulated manner and to avoid any further delays in the implementation of the Paris Agreement.

4.1. Article 6 – International Emissions Trading

After years of debate, the negotiations under Article 6 on the elements of an international emissions trading scheme have been agreed at COP26. The essence of the system is that countries can offset their emissions through financial support of emission reduction projects in other countries without reducing their own emissions. The basic idea of the system causes also the majority of criticism, as it does not provide incentives to reduce emissions for big emitters, in essence, rich countries can buy the right to continue to emit greenhouse gases. Pre-Paris regimes have also allowed for a number of abuses, such as double counting of allowances or the build-up of hot air. The latter has been a source of controversy even within the EU, as some Eastern European Member States have fought to allow previously unused allowances to be transferred to the Paris Agreement system to meet their increased emission reduction targets. Fortunately, this debate has gone in a positive direction, with the EU and its Member States finally committing themselves to meeting their 2030 targets without the use of international emissions trading.

The final agreement involved many compromises. No share of proceeds is levied on bilateral trade between states, but 5% of the value traded under the UN system will be spent on supporting developing countries. In addition, 2% of allowances are continuously withdrawn from the scheme, encouraging countries to further reduce emissions. The double-counting was ultimately resolved by Japan’s proposal that the seller decides whether to report the units to meet its targets, and if not, the buyer can deduct them. Unfortunately, hot air can still get into the system; all unused allowances after 2013 can be transferred to the Paris scheme, seriously reducing the real emission reduction potential of the national commitments. Adopting detailed rules is a fundamentally important step, but for green organizations, who see all such schemes as just carbon leakage, the system is generally disappointing because it leaves enough room for countries and companies to continue emitting greenhouse gases.

4.2. Transparency

The transparency framework is a key element of the Paris Regime, but also of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change as a whole, as only continuous and high-quality reporting can monitor countries’ emissions and commitments. This is why it was important to standardize the previously highly fractionalized reporting system. So far, developed and developing countries have reported under different conditions, making it difficult to monitor and compare their emissions and implementation. COP26 also adopted common reporting tables for the compilation of national GHG inventories, common formats for reporting on NDC compliance, and monitoring of funding, technology transfer and grants, while providing reliefs and support for countries with limited capacities.

4.3. Common timeframes

Prior to the Paris climate conference, countries have already announced their intended nationally determined contributions. However, these have not yet been done on a uniform timeline; for example, the European Union and its Member States have submitted commitment up to 2030, while there have been countries that have a 2025 target. After many years of discussions, COP26 has agreed on a common timeframes for Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). The next set of targets to be submitted in 2025 should have targets up to 2035, while the following one to be submitted in 2030 should go up to 2040. This will also make it easier to monitor and compare commitments and coordinate the review every 5 years under the Global Assessment. This could lead to a change in legislation for the EU and its Member States, as the Governance Regulation governing the preparation of National Energy and Climate Plans sets a 10-year timeframe for Member States (in line with the original EU 2030 commitment) that could be reviewed by Member States once every 10 years.

5. The role of Central European Member States and the EU in the negotiations

On behalf of the Member States, a unified EU delegation negotiates at the climate conferences based on a previously agreed continuously updated common EU position. It should be emphasized here that Member States have no national international commitment under the UN system, they participate in the EU’s unified commitment (at least -55% emission reductions by 2030) and the related debates are taking place within the EU. Importantly, however, the EU has remained united throughout during the COP26 and internal climate policy debates have not weakened international positions, as has sometimes been the case in previous negotiations for example under Article 6 discussions.

The countries of the Visegrád group were all represented on the highest level during the COP; Andrej Babiš Prime Minister of Czechia, János Áder Persident of Hungary, Mateusz Morawiecki Prime Minister of Poland and Zuzana Caputova President of the Slovak Republic were present. Hungarian media and opposition have criticised Viktor Orbán not to be present, but international climate issues are usually left to Áder, while Orbán deals with EU internal topics. All leaders present at the COP have signaled the need of urgency to gear up the fight against climate change, however there were also some disappointments raised on EU policies. The countries have joined some initiatives during the COP, all of them signed the Leaders Declaration on Forests and Land Use committing to protect forests, while none of them joined the Global Methane Pledge.

However, as the EU, as a political organization has joined the latter one as well, we can be certain that the Visegrád group will be part of the implementation as well. However, once again, the EU has not really played a decisive role and has not been able to help the North-South rapprochement. At COP26, the “big players” were the US, China, and India. However, the big question for the future is whether the European Commission or some Member States will want to increase the common EU 2030 target again by 2022. If so, we can expect heated debates within the EU, since the eastern Member States are already debating the implementing rules for the current at least -55% pledge of the EU.